Elestor - Hydrogen-Iron Flow Battery for Renewable Energy Storage

The Elestor Hydrogen-Iron Flow Battery represents a significant advance in renewable energy storage solutions, enabling a sustainable transition towards clean energy systems. Utilizing hydrogen and iron, both plentiful and cost-effective materials, the battery stores renewable energy over extended periods, addressing the challenges associated with intermittent power generation. The flow battery's key feature is its scalability: power output is determined by the membrane's surface area, while storage capacity is defined by the reservoirs' volume. This modularity allows for optimized energy storage solutions tailored to specific power and capacity requirements, an advantage over traditional systems where these parameters scale together. Elestor's focus on conducting thorough life cycle analyses and integrating future hydrogen infrastructures enables its technology to minimize environmental footprints and reduce total system costs. With a robust design, high energy density, and innovative integration capabilities, this flow battery technology supports the burgeoning green hydrogen infrastructure and significantly contributes to decarbonization efforts.

The choice of hydrogen and iron

Elestor is powered by a mission to build a storage system with the lowest possible storage costs per MWh. With this as our cornerstone criteria, and it is one that can only be met with inexpensive chemistries if we are to take full advantage of the typical flow battery features, our behind the scene R&D wizards have explored a variety of chemistry combinations.

In theory, there are many different chemistries that could be used to design a flow battery, but to date we have only come across two that could work in the real world. One relies on hydrogen and bromine as active materials, and this solution remains great on paper, but we have come to the conclusion that there is another, even better so-called redox coupling, namely hydrogen-iron, which is better suited to real-world applications and the present geopolitical environment.

Like bromine, iron is obviously abundantly available all over the world; indeed, arguably slightly more so than bromine, which is extracted from sea water and thus not abundant far from the sea. The importance of selecting a redox coupling made up of two materials that are not restricted by geographical availability has become even more important during the last couple of years. Given the ongoing geopolitical turbulence, it is more important than ever that we create a resilient and self-reliant energy storage solution that is independent from and cannot be dominated by a small group of suppliers, or indeed by a single or a small number of countries. Iron, hydrogen and bromine all have these qualities, unlike other materials such as lithium, cobalt and vanadium, which are presently more popular with makers of battery solutions in spite of their scarcity.

By going for abundant rather than scarce materials, we have by definition chosen very low-priced active materials. Not only presently, but for decades to come, indeed, even when large volumes will be required for high-volume production of hydrogen-iron flow batteries.

Another advantage of selecting a hydrogen and iron-sulphur redox couple, is that these enable a high power density [W/m2] as well as a high energy density [kWh/m3], both contributing to the reduction of storage costs per MWh.

Sure, this combination’s power and energy density is not quite as impressive as that of a hydrogen and bromine redox couple, but it still beats all other rival flow battery chemistries, while at the same time it comes with several other advantages.

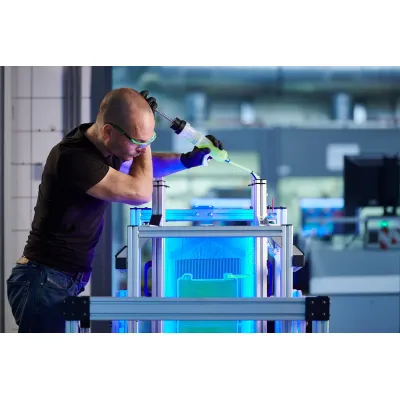

The heart of all Elestor’s storage systems is the cell stack. This stack consists of a number of individual electrochemical cells, as shown above, connected in series.

Each membrane in this stack is in contact with the electrolyte circuit, an aqueous iron-based solution (FeSO4).

On the other side, each membrane is in contact with a hydrogen (H2) gas circuit. Both active materials circulate in a closed loop along their own respective side of the cell. The electrolyte (aqueous FeSO4 solution) and hydrogen (H2) circuits are separated by a proton-conductive membrane.

Flow batteries were initially developed in the 1960s by The USA’s National Aeronautics and Space Administration, better known simply as NASA. But it wasn’t until the 1980s that their popularity picked up speed, after they were proven to last for more than 10,000 charge/discharge cycles. Along with the continuously growing installed base of renewable energy systems, most notably solar and wind power, it has become obvious that the need to store large, indeed very large, quantities of electrical energy for longer periods of time is growing equally quickly. Such energy storage is essential if we are to achieve a total transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy.

The term flow battery covers a family of storage systems where each one will apply the same fundamental working principle, while using different combinations of active materials. The heart of a flow battery is a so-called electrochemical cell, which is a multi-layer assembly of an ion-selective membrane, catalyst layers and electrodes.

A complete flow battery system, also referred to as a redox flow battery or RFB, is constructed around such electrochemical cells, where chemical energy is provided by the chemical reaction of two active materials. The active materials are contained within the system, separated by the membrane, and circulate in a closed loop, each one in their own respective space.

When an electrical power source is connected, which is when the battery is charging, a chemical redox reaction starts. Ion exchange then occurs through the membrane, resulting in electric current. During discharge, when applying an electrical load, the reverse chemical reaction takes place.

The voltage of the electrochemical cell is determined by the Nernst equation and ranges in practical applications from 1.0 to 2.2 V, depending on the selected active materials.

In order to increase the total electrical power, individual electrochemical cells are stacked, which is another way to say that the cells are electrically interconnected in series. To design systems with (very) large power levels, multiple stack assemblies can be interconnected.

The power [MW] of a flow battery system, as depicted above, is determined by the surface area of the ion-selective membrane, while the capacity [MWh] of the system is determined by the volume of the catholyte and anolyte reservoirs.

The fact that the membrane surface area and the reservoir volumes can be dimensioned individually highlights one of the most distinguishing properties of flow batteries, as opposed to traditional electricity storage systems where power [MW] and capacity [MWh] scale simultaneously.

Elestor is powered by a mission to build a storage system with the lowest possible storage costs per MWh. With this as our cornerstone criteria, and it is one that can only be met with inexpensive chemistries if we are to take full advantage of the typical flow battery features, our behind the scene R&D wizards have explored a variety of chemistry combinations.

In theory, there are many different chemistries that could be used to design a flow battery, but to date we have only come across two that could work in the real world. One relies on hydrogen and bromine as active materials, and this solution remains great on paper, but we have come to the conclusion that there is another, even better so-called redox coupling, namely hydrogen-iron, which is better suited to real-world applications and the present geopolitical environment.

Like bromine, iron is obviously abundantly available all over the world; indeed, arguably slightly more so than bromine, which is extracted from sea water and thus not abundant far from the sea. The importance of selecting a redox coupling made up of two materials that are not restricted by geographical availability has become even more important during the last couple of years. Given the ongoing geopolitical turbulence, it is more important than ever that we create a resilient and self-reliant energy storage solution that is independent from and cannot be dominated by a small group of suppliers, or indeed by a single or a small number of countries. Iron, hydrogen and bromine all have these qualities, unlike other materials such as lithium, cobalt and vanadium, which are presently more popular with makers of battery solutions in spite of their scarcity.

By going for abundant rather than scarce materials, we have by definition chosen very low-priced active materials. Not only presently, but for decades to come, indeed, even when large volumes will be required for high-volume production of hydrogen-iron flow batteries.

Another advantage of selecting a hydrogen and iron-sulphur redox couple, is that these enable a high power density [W/m2] as well as a high energy density [kWh/m3], both contributing to the reduction of storage costs per MWh.

Sure, this combination’s power and energy density is not quite as impressive as that of a hydrogen and bromine redox couple, but it still beats all other rival flow battery chemistries, while at the same time it comes with several other advantages.

The heart of all Elestor’s storage systems is the cell stack. This stack consists of a number of individual electrochemical cells, as shown above, connected in series.

Each membrane in this stack is in contact with the electrolyte circuit, an aqueous iron-based solution (FeSO4).

On the other side, each membrane is in contact with a hydrogen (H2) gas circuit. Both active materials circulate in a closed loop along their own respective side of the cell. The electrolyte (aqueous FeSO4 solution) and hydrogen (H2) circuits are separated by a proton-conductive membrane.